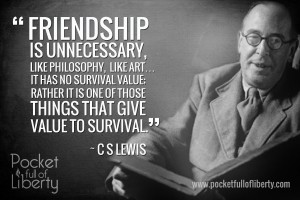

The Moral Argument for God by C.S. Lewis

The Moral Argument for God by C.S. Lewis

Lewis’ Moral Argument. The most popular modern form of the moral argument was given by C. S. Lewis in Mere Christianity. He not only gives the most complete form of the argument in the most persuasive way, but he also answers major objections. The moral argument of Lewis can be summarized:

1. There must be a universal moral law, or else: (a) Moral disagreements would make no sense, as we all assume they do. (b) All moral criticisms would be meaningless (e.g., “The Nazis were wrong.”). (c) It is unnecessary to keep promises or treaties, as we all assume that it is. (d) We would not make excuses for breaking the moral law, as we all do.

2. But a universal moral law requires a universal Moral Law Giver, since the Source of it: (a) Gives moral commands (as lawgivers do). (b) Is interested in our behavior (as moral persons are).

3. Further, this universal Moral Law Giver must be absolutely good: (a) Otherwise all moral effort would be futile in the long run, since we could be sacrificing our lives for what is not ultimately right. (b) The source of all good must be absolutely good, since the standard of all good must be completely good.

4. Therefore, there must be an absolutely good Moral Law Giver.

The Moral Law Is Not Herd Instinct. Lewis anticipates and persuasively answers major objections to the moral argument. Essentially, his replies are:

What we call the moral law cannot be the result of herd instinct or else the stronger impulse would always win, but it does not. We would always act from instinct rather than selflessly to help someone, as we sometimes do. If the moral law were just herd instinct, then instincts would always be right, but they are not. Even love and patriotism are sometimes wrong.

The Moral Law Is Not Social Convention. Neither can the moral law be mere social convention, because not everything learned through society is based on social convention. For example, math and logic are not. The same basic moral laws can be found in virtually every society, past and present. Further, judgments about social progress would not be possible if society were the basis of the judgments.

The Moral Law Differs from Laws of Nature. The moral law is not to be identified with the laws of nature. Nature’s laws are descriptive (is), not prescriptive (ought) as are moral laws. Factually convenient situations (the way it is) can be morally wrong. Someone who tries to trip me and fails is wrong, but someone who accidentally trips me is not.

The Moral Law Is Not Human Fancy. Neither can the moral law be mere human fancy, because we cannot get rid of it even when we would like to do so. We did not create it; it is impressed on us from without. If it were fancy, then all value judgments would be meaningless, including such statements as “Hate is wrong.” and “Racism is wrong.” But if the moral law is not a description or a merely human prescription, then it must be a moral prescription from a Moral Prescriber beyond us. As Lewis notes, this Moral Law Giver is more like Mind than Nature. He can no more be part of Nature than an architect is identical to the building he designs.

Injustice Does Not Disprove a Moral Law Giver. The main objection to an absolutely perfect Moral Law Giver is the argument from evil or injustice in the world. No serious person can fail to recognize that all the murders, rapes, hatred, and cruelty in the world leave it far short of perfect. But if the world is imperfect, how can there be an absolutely perfect God? Lewis’ answer is simple: The only way the world could possibly be imperfect is if there is an absolutely perfect standard by which it can be judged to be imperfect (see MORALITY, ABSOLUTE NATURE OF). For injustice makes sense only if there is a standard of justice by which something is known to be unjust. And absolute injustice is possible only if there is an absolute standard of justice. Lewis recalls the thoughts he had as an atheist:

Just how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust. . . . Of course I could have given up my idea of justice by saying it was nothing but a private idea of my own. But if I did that, then my argument against God collapsed too—for the argument depended on saying that the world was really unjust, not simply that it did not happen to please my private fancies. Thus in the very act of trying to prove that God did not exist—in other words, that the whole of reality was senseless—I found I was forced to assume that one part of reality—namely my idea of justice—was full of sense. [Mere Christianity, 45, 46]

Rather than disproving a morally perfect Being, the evil in the world presupposes a perfect standard. One could raise the question as to whether this Ultimate Law Giver is all powerful but not whether he is all perfect. For if anyone insists there is real imperfection in the world, then there must be a perfect standard by which this is known.

Geisler, N. L. (1999). In Baker encyclopedia of Christian apologetics (p. 500). Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

0 Comments